(That ‘irreplaceable censor cut’ has, of course, now been replaced: the reference being to the scene long thought lost, in which the Monster befriends a young girl and accidentally drowns her.)

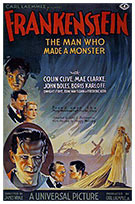

The iconic image of Boris Karloff as the Monster dominates the picture:

‘…audiences must have been aware that they were to witness the birth of a new star… and Karloff does not disappoint… what wonders of expression [he] can bring into that totally false face, especially when compared with the stolid comic-strip vacuum offered by his several successors. It is almost true to say that every frame in which he appears makes a still picture worth hanging on the wall.’

Halliwell sums up director James Whale’s seminal film:

‘Many more recent films date badly, but Frankenstein seems to have lost none of its stark style, though the romantic scenes, in which Whale clearly took no interest, might have been treated more realistically. It remains more truly frightening than any of our modern horror sagas filled with bloody corpses and severed eyeballs. And it retains this effect because Whale intuitively used his camera to get through to fears and hopes which lurk within all of us; also because in Colin Clive and Boris Karloff he chose two actors who in these particular roles could not have been bettered.’

LH failed to see this film on its 1937 re-issue with Dracula, at the Embassy in Bolton, because it had been re-certified as ‘H’ for Horror, meaning adults only were admitted (he was only eight at the time). It may have been many years later, when at college in Cambridge, that he finally caught up with it. He comments that it was –

‘…made in 1931 before the talkies had learned their technique, it was necessarily a stark and primitive film, marred occasionally by backcloths and by one irreplaceable censor cut, and rather obviously lacking the final brush strokes of background music. But it didn’t lack humour, or vigour, or cinematic ideas.’

Halliwell |

| Frankenstein |